The 20th century saw the continuation of unprecedented resource extraction and economic development throughout the Abitibi-Temiscamingue region. Large scale industry expansion and community infrastructure expansion pushed into the far reaches of Algonquin territory.

The Kitchisipi (the Ottawa River) and its tributaries were dammed. When pulp for paper became the basis of the new timber economy, mills sprang up to meet the demand, and clear-cut logging commenced to support the increasing demand of the mills.

Despite the generation of wealth and technological advances, the Algonquin people shared in neither the bounty nor the profits that accompanied the often dramatic changes to our landscape.

Colonization

After 1900, a promotional campaign, sponsored by the Roman Catholic Church and supported by the Quebec government, was encouraging Francophones to repatriate from the North-Eastern United States and Western Canada. The Abitibi-Temiscamingue region was designated as a “colonization zone”, wherein large swaths of land were available for re-settlement. To ensure the steady inbound stream of settlement, the Quebec government invested heavily in new roads and farm machinery for new farmers.

In conjunction with the provincial agricultural stimulus plan, the department of Indian Affairs encouraged Algonquin communities to shift their economic and subsistence focus from hunting and trapping to farming. However, progressing and succeeding at an agrarian lifestyle was nearly impossible. As a local Indian Ganet of the time noted, the government failed to provide us with “the machinery necessary...really [the Algonquins] have not the means to clear their farms and work them in such a manner as to get the greatest returns out of them.” Not to mention, all the prime farmland was given to white settlers.

Just like Quebec, the province of Ontario was also encouraging settlers to take up farming in our region. At towns like Haileybury, New Liskeard and points north, the initiative proved to be successful. By 1905 the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway was operating from North Bay to Liskeard. The railway facilitated even greater waves of immigration into the region, and its popularity effectively put an end to steamboat travel on Lake Temiscaming.

The Cobalt silver rush in the early 1900s drew people into the area in large numbers to prospect, stake claims and work in the mines. Increased mineral exploration led to mineral claims and mining allocations for new developments. Add to that, the pulp and paper industry was steadily attracting settlers. The net result of this influx of settlers was that, as Algonquins, we became a minority in our own territory.

Our lands were once a fisherman’s and hunter’s paradise.

In the late 1800s, the government of Quebec began selling off lakes, rivers and hunting territories to operators of exclusive hunting and fishing clubs. By the early 20th century, our territory was dotted with ‘no-go zones’ by such organizations as the Dumoine Fish and Game Club and the Caughnawaga Fish and Game club. Often these organizations were controlled by lumber barons or other powerful business interests from the United States, Toronto and Montreal.

Non-Algonquin sportsmen poured into our region. Unregulated harvesting by non-Algonquin hunters and trappers ultimately conflicted with our own subsistence. Our nutritional mainstay of fish and game was in serious decline. As our lands were being inundated with Canadian and American leisure-class sportsmen, our Algonquin leaders tried to get lands set aside for our own hunting and trapping purposes. But the province’s tourism policies favoured the fishing and hunting industry over Algonquin subsistence.

By 1920, beaver and other fur-beavers were almost wiped out. The government's response was to impose “closed-seasons” and other harvesting restrictions. Our people were forced to make a living from the land by hunting in secret lest we got caught and fined and sent to jail. In the 1940s, the province introduced the registered trapline system, resulting in a huge chunk of our traditional trapping areas being licensed out to non-Algonquins. After 1945, Quebec began issuing exclusive licenses to control tourist outfitting on certain lakes. These activities generated tremendous revenues for Quebec.

By mid-century our people were utterly impoverished.

The government of Quebec also sponsored an ill-fated policy of licensing unregulated commercial fishermen on Lake Temiscaming and Lake Kipawa. Under little-to-no supervision, these commercial fisherman operated tug boats with large nets that were dragged beneath the water, scooping up everything in their paths and destroying valuable fish habitats. By 1903, despite complaints that Lake Temiscaming was being cleaned out of its fisheries, Quebec made no effort to protect the fish stocks. By the time the province finally did act, it was too late: the fish stocks had been depleted to near irreparability.

During the timber trade, tugboats went up and down lake Temiscaming hauling log booms from up the Montreal River and Lac Quinze down to the Tembec mill, here in Temiscaming. One of our Elder Band members, Councilor Gerald Robinson, recalls working on the ‘Pj Murer’ from 1973 to 1977, Gerald hauled log booms from Notre-Dame-du-Nord down to the Temiscaming mill at Opemica.

“I worked in the engine room. It was loud and hot. Me and the new guy had to work all night, and we’d sleep all day. . . so we didn’t get to see much”, recalls Gerald.

“On our last run, I got to see the Old Fort in Ville-Marie. . . that was October 1977. We made record time from Notre-Dame-du-Nord to Opemica depot. 54 hours!”.

Indian and Northern Affairs

As Indian Affairs reports reveal, our land base was shrinking significantly in the early twentieth century. In the case of the reserve at Temiscaming, the Indian agents report for 1913 shows that the reserve was originally intended to comprise an area of 38,400 acres; but in no time, the land available for Algonquin use had shrunk to only 14,318 acres. Further, with a lack of government support and monies to assist them in their transition to the new agrarian lifestyle, they had as of 1914 only the means to establish themselves and their new farms on a mere 3.710 acres.

Though the government chalked this situation to routine “land surrenders” to the Crown, the fact was our people were under severe pressure at the hands of unscrupulous speculators and agents to relinquish our title. So many obstacles were placed in their way as they tried to carve out a new life on the reserve that, in many cases, their continued occupation of lands in some areas become untenable. Deprived of the government support and suffering from both disease and economic ruin, in many ways our ancestors were in no position to fight against the waves of colonization that were hitting their lands at the beginning of the twentieth century.

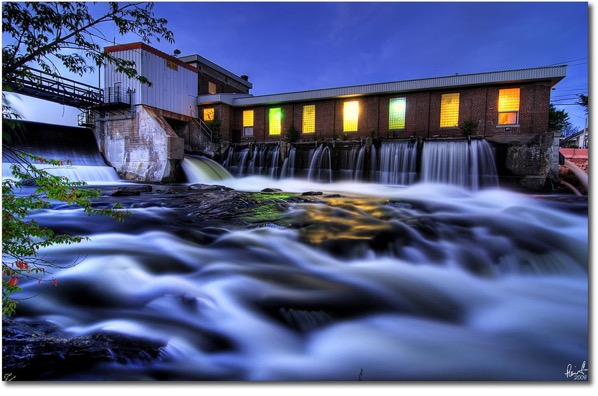

Dams

In the early 20th century, the forest industry was pressing the federal government to regulate water levels on the Ottawa River and its tributaries, arguing the necessity for dams to control spring flooding and make it easier to float timber down to Hull. in 1908, an engineer from the department of public works recommended that the federal government build a series of control dams throughout that Ottawa basin. Work that would take decades to complete began in 1909. One dam was constructed at the head of the Long Sault. Two others were built on Lake Kipawa - one at Gordon Creek and one at Laniel. Another dam was erected at the exit of Lac des Quinze at what is now Angliers.

There was absolutely no consultation with our people, and many areas of our territory were subsequently flooded.

With the construction of control dams in the upper Ottawa basin, the potential for hydroelectric development was realized. In 1918, the dam on Gordon creek was renovated to generate power for the new Riordan pulp mill in Temiscaming. Several more hydroelectric dams were built along the Ottawa River and its tributaries. They would provide power for mines, pulp mills and provincial electricity markets.

While the dam spurred industrial development throughout the region, they also caused extensive shoreline erosion and obliterated fish habits. In many parts of Lake Kipawa and elsewhere on the Ottawa River and its tributaries, fish stocks were so depleted that they could no longer be relied upon to feed us.

Pulp and Paper

By the late 1800s the Ottawa basins square timber trade was declining. Local sawmills were facing increased competition from west coast producers. Enter Charles Riordan, an American industrialist who would breathe new life into the forestry industry by utilizing a neglected tree species (spruce) to make a new product: pulp.

In 1886, Riordon pioneered North America's chemical (sulphite) process for converting wood fibre to pulp. Twelve years later, he built a mill at Hawkesbury, Ontario, but quickly faced a dwindling supply of spruce, so he began looking for another mill site further up the ottawa valley. The location he chose was next to Alex Lumsden’s buildings, along with the hydro- electric plant which had powered the mill and settlement. The old wooden Lumsden dam was upgraded in size and made of cement. Riordan's company began its “Kipawa Mill” operations in 1918.

Riordan's Pulp and Paper Company developed a model town for the workers and their families, following the natural conditions of the hill above the mill site. The new self-described “Garden City” was named Temiscaming. Like all company towns, the size and location of each house reflected the job ranking of its occupant. Management got the best houses, supervisors and skilled tradesman the second best, while manual labourers got assigned to whatever was left over.

In 1925, Riordan's entire Temiscaming operation was purchased by the Canadian International Paper Company (the CIPC). For the next half-century the CIPC ran both the hydro-dams and pulp mills with varying degrees of success. In 1971, the CIPC announced it would be closing the Temiscaming mill, the town's economic lifeblood, and did so the following year.

The mills former workers and Temiscaming residents fought to save their jobs. With the help of a few private investors, their efforts resulted in the formation of a new company called Tembec. Tembec bought the CIPC’s installations and the mill’s operations resumed in 1973.

Tembec is still operational today, but it was bought out by Rayonier Advanced Materials in 2017. Its operations extend throughout North America and France. With worldwide sales of approximately $2 billion and some 6,000 employees, it operates over 30 market pulp, paper and wood product manufacturing units and produces silvichemicals from by products of its pulping process and specialty chemicals. As of late, the mill has worked closely with our band to harmonize sectors in our territory of interest so that harvesting plans can be mutually agreed upon.

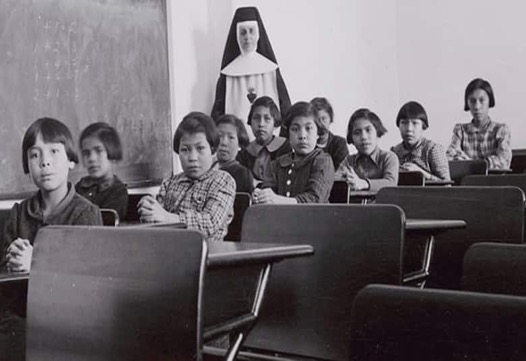

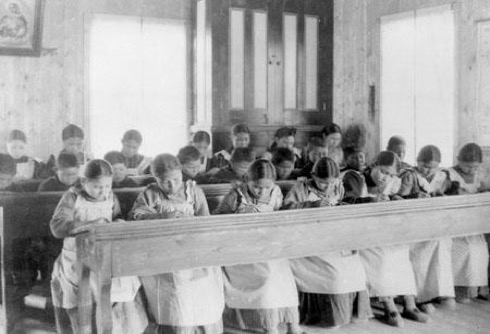

Residential Schools

In the early 1870s the Canadian government implemented Indian Residential Schools and Indian Day Schools. These were institutions designed to “Kill the Indian in the Child.” The schools were funded by the federal government. The Catholic, Anglican, United and Presbyterian churches were charged with the schools’ day to day operations. The basic difference between the Residential Schools and Day Schools was that students of the Indian Day schools could return home in the evenings.

Until the last school closed in 1996, a total of 132 Residential schools operated throughout the country (with the exception of Newfoundland, New Brunswick and PEI). Over 150,000 Aboriginal children received the Indian Residential schools particular brand of education. Another 70,000 Aboriginal children were education in Indian Day Schools.

The Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement: By the turn of the century, the number of lawsuits brought against the Government of Canada and the churches involved in the Residential Schools totalled over 10,000. Pressure was mounting to expedite a resolution to address the legacy of the Indian Residential School System. With collaboration from representatives of the federal government, former students of the residential schools, the churches, the assembly of First Nations, and other Aboriginal organizations, the proceeding resolution was manifest in the form of the Indian Residential School settlement agreement (IRSSA) - the largest class action settlement in Canadian history. The terms negotiated in the IRS came into effect on September 10 2007. The monetary distribution of the IRSSA breaks down into five components:

- Common Experience payment (CEP) - $10,000 to each survivor who attended a Residential school, plus an additional $3,000 for every subsequent year in attendance.

- Truth and Reconciliation- $60 million to establish a truth and reconciliation commission.

- Independence assessment process (IAP) - $5,000 to $275,000 to survivors who can demonstrate loss of income as a result of sexual, physical, and/or psychological abuses

- Commemoration - $20 million for national and community-based events and memorials to commemorate the legacy of Indian Residential schools,

- Healing - $125 milion to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Addendum: Survivors of Indian Day Schools were excluded from the Indian Residential School settlement agreement as well as the Apology. In July of 2009, Indian Day School survivors filed a $15 billion class-action lawsuit against the federal government for damages ensued from their Indian Day School attendance.

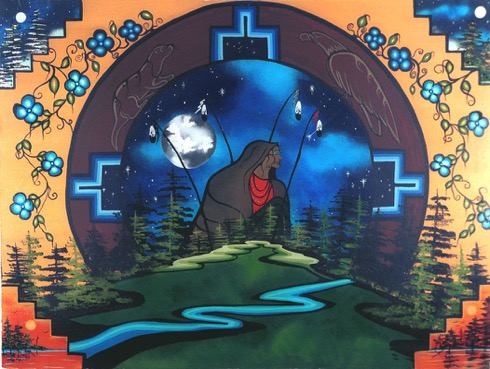

Our Common Reality

The earth is like a mother and a child; she gives and provides all the amenities that are required to thrive; but she is also fragile, delicate, and she needs to be properly cared for. If the stewardship of the land is health, so too will healthy communities grow on that land. For let us not forget that we are part of the land, and not separate, domineering rulers over it.